The world is full of plants that affect our state of mind.

Humans have been benefiting from these plants and their effects since ancient times. One of these substances, derived from the root of the Piper methysticum ("intoxicating pepper") plant, is kava.

Kava isn’t quite mainstream yet in the West, but there’s definitely a growing scene. You may have come across a kava bar if you live in a big city. However, it’s actually been used for centuries in the Pacific Islands, where it is frequently consumed in traditional ceremonies and social settings.

The plant is known for making you calm and relaxed. It kind of feels like smoking weed or drinking alcohol, but also not really. It’s relaxing without having intense mind-altering effects. That said, it is very bitter and not tasty unless mixed with juice (but this is subjective). It also makes your mouth numb and tingly, and this effect can be quite pronounced.

One of the primary traditional uses of kava is for social gatherings. People have used it for welcoming guests, important occasions, and even conflict resolution.

Like alcohol, kava is believed to enhance sociability. However, although studies have demonstrated kava’s anti-anxiety and pain-relieving properties (Sarris et al, 2020), its effects on social bonding had yet to be scientifically studied.

We conducted the first small randomized-controlled trial on this topic. Many thanks to our friends at the MatKat Foundation (a German educational non-profit, no relation to kava) for supporting this initiative.

Our study is modeled after a widely-cited study demonstrating the social lubrication effects of alcohol (Sayette et al, 2012). We invited participants to a gathering where they consumed a randomly assigned drink (kava, alcohol, or juice) and chatted in groups of 3 strangers for 30 minutes, then filled out a survey about their level of connection to the group.

How did we make it so that people couldn’t tell what they were drinking?

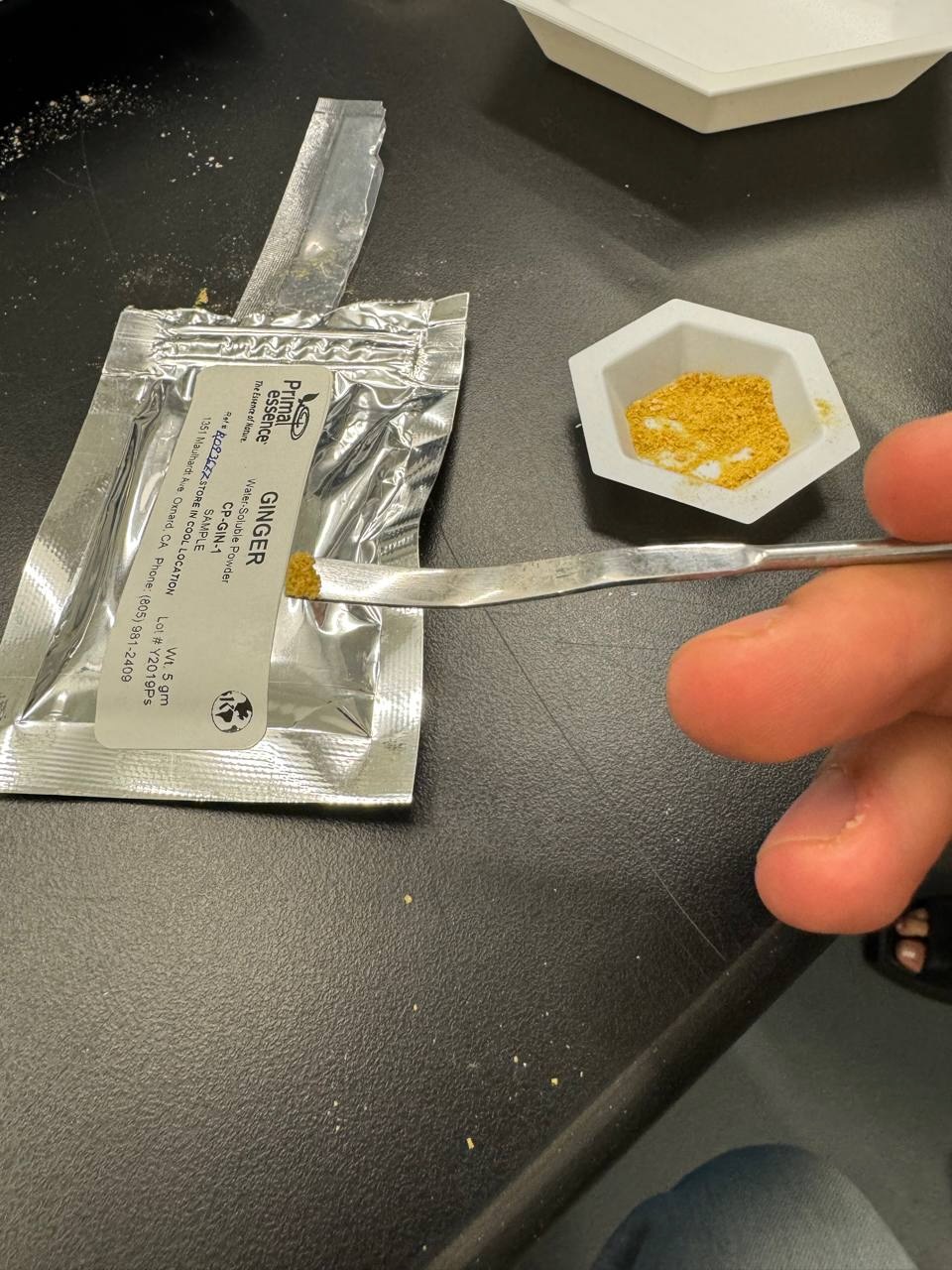

We experimented with drink recipes that would mask the strong flavors of kava and alcohol. We made liberal use of both concentrated ginger powder and a potent Stevia sweetener to conceal the taste differences. Fortunately, this worked relatively well, with only 50% of participants in the study correctly guessing their drink. See the “Study Quality Assessment” section below for more details.

Alcohol recipe: 1 oz (30mL) vodka + 131mL Goya mango nectar + 2 scoops ginger extract

Kava recipe: 1.5 teaspoons kava powder + 131mL Goya mango nectar + 2 stevia scoops

Placebo recipe: 131mL Goya mango nectar + 2 scoops ginger extract

Determining the right dose for each beverage was challenging, but we aimed to use amounts that were effective while remaining hard to detect. For the kava drink, we used 1.5 teaspoons of kava powder—slightly below the typical traditional serving of 2 to 4 teaspoons. For the alcohol drink, we served 1 oz of vodka, which is just under a standard drink (1.5 oz).

We held the study as a social event where participants were invited to have a drink and socialize with new acquaintances.

They were informed that they would be receiving either alcohol, kava, or juice, but they would not know which, and they were not informed of the outcome that we would be measuring. Participants spoke in randomly assigned groups of three for 30 minutes and then filled out a survey about their experience. We instructed them to introduce themselves and respond to an introductory discussion prompt.

We held two of these events and got a total of 26 participants divided into 9 social groups (3 per group, except for one lost survey response), with 3 groups assigned to each treatment (kava, alcohol, juice).

The image below is a preview of our new study assessment framework, currently in development, applied to this study. It defines levels of research quality among three dimensions (Reproducibility, Power, and Rigor) and places studies within a broader research context (Exploratory, Emerging, or Established). More information about the framework coming soon.

There is limited prior research on kava, and none specifically investigating its effects on social bonding. Compounds called kavalactones act as positive allosteric modulators of GABA receptors, increasing GABA’s calming effect on the nervous system. Notably, research on isolated kavalactones (e.g. kavain) shows they boost various GABA receptor subtypes without binding to the same site as benzodiazepines, indicating a distinct mode of action that produces relaxation without heavy sedation (Chua et al, 2016). This suggests a plausible pathway through which kava could influence social processes.

Reproducibility: The study has a repeatable protocol, no proprietary dataset, and easily accessible materials (kava is not a controlled substance in the U.S.).

Power: Our study included 26 participants divided into 9 social groups (3 per group, except for one lost survey response), with 3 groups assigned to each treatment (kava, alcohol, juice). While we met our goal of 3 groups per treatment, we originally planned for 5 participants per group to reduce variability. A previous study on alcohol and social bonding (Kirchner, 2006) found significant results (p<0.05) on the PGRS using 9 groups of 3 participants per treatment. Our study was likely underpowered because we had fewer groups and fewer total participants, which may have limited our ability to detect significant differences.

Rigor:

Long story short, we found no significant differences between beverage groups for any of the measures.

To test whether beverage condition (kava, alcohol, or juice) influenced participants’ feelings of social connection and engagement, we did one-way ANOVAs on four outcome measures: the question subset from the Perceived Group Reinforcement Scale (PGRS), the Inclusion of Others in the Self (IOS) scale, and the pleasure and engagement subscales of the ENJOY scale.

We also ran mixed effects models to account for the fact that participants were grouped in triads. These models tested whether drink type (kava, alcohol, or juice) predicted scores on the PGRS and IOS, while also including gender, prior knowledge of the drink, and session as additional factors. Drink type was not a significant predictor in either model (e.g., for PGRS: alcohol vs. kava, b = –0.10, p = .90; juice vs. kava, b = 0.01, p = .99), and none of the covariates were statistically significant. The random effect for group had minimal variance (e.g., PGRS group variance = 0.25), suggesting that group membership did not strongly influence participants’ responses.

We consulted with a respected kava expert to get his thoughts on these results. We wanted to share some of his comments here as a complement to our data.

In the Pacific Islands, kava is consumed in communal settings to promote relaxation and interpersonal harmony. It is believed to enhance connection among those who drink it. In conducting this study, we wanted to put this claim to the scientific test.

Alcohol is a double-edged sword—while it can lower inhibitions and encourage social interaction, it also comes with well-known health risks, the potential for addiction, and negative social consequences. If kava could provide these benefits without as many risks, it would be a powerful alternative for humans to unwind and connect.

However, our study did not find evidence that kava enhances social bonding.

That said, there are several reasons why our findings should be interpreted with caution. Social bonding is difficult to quantify, especially through brief surveys, and individual variability in mood and personality likely played a significant role in responses. The setting may also matter greatly—kava’s calming effects may promote a slower, more subtle sense of connection that develops through shared ease, rather than immediate talkativeness. In a brief 30-minute interaction with strangers, that slower bonding process may not have had time to emerge.

Dose may have been another key limitation. We used a modest serving of 1.5 teaspoons of instant kava, which may not have been sufficient for participants—particularly first-time users—to feel meaningful effects. Unlike alcohol, kava lacks a standardized dosing framework, and its effects may be more dependent on context, consumption method, and individual sensitivity.

We grapple with the implications of pursuing and publishing exploratory work. On the one hand, we believe in transparency, and that all evidence – particularly that which is thoughtfully collected – has epistemic value. On the other hand, we know that there is a risk of other researchers, the media and the public drawing hasty conclusions, as there is always a gap between raw data and the way that data is presented.

What if a world of widespread kava use would truly be healthier, happier, and more socially bonded? What if our study, with its flaws and limitations, unintentionally dissuades researchers from doing more studies and discovering this potential?

This study should not be the be-all and end-all on the question of kava’s effects on social bonding. If we were to conduct further research, we should do a study closer to the context of how kava is used in Pacific Islands contexts, and even in American kava bar contexts. We should also seek to understand its role in cultural practices.

Science is often seen as a step-by-step march towards Truth, but in reality it requires intuitive observation and iteration. Noticing a correlation can spark insight about possible causality, and causal theories can tell you where to search for observable relationships.

Ultimately, we feel that all experiments contribute additional samples of the universe to the collective pool of information, and should be shared with as much integrity and clarity as possible. While this initial exploration of the social effects of kava did not yield a statistically significant result, we encourage further research in this area, and hope that our initial foray will help subsequent researchers do it better.

Subscribe to the Journal

Learn more about Cosimo Research

Join our active study: The Big Taping Truth Trial